ENTREPRENEURSHIP DEVELOPMENT

Development is no longer a natural phenomenon, nor is it purely based on the resource endowment of a region. It has to be brought about by planned action and through appropriate strategies. We have the glaring examples of countries that have immense natural resources, but remain under-developed and also countries that have industrialized with the least of natural resources or land area. The nature of human intervention is increasingly becoming critical in the development process. And such interventions should be responsible enough too so that life on earth is sustainable.

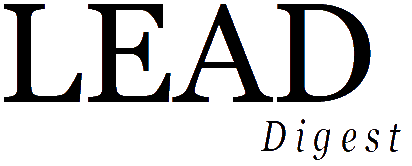

The development process itself is a cycle, which needs stimulatory, support and sustaining inputs. These inputs, which are from different domains of a socio-economic framework, will have to be provided cutting across traditional sector barriers. The multifarious factors of interdependencies have to be considered from a holistic angle. For instance, any attempt to nurture and sustain industrial development need to consider the social and environmental consequences and should also be clear about the desired socio-economic outcomes. Yet another factor is the quality of entrepreneurs, including its linkages with the educational system.

While the existing educational infrastructure in most countries guarantees basic schooling, opportunities for higher education are often limited or expensive. An extension of the pipeline of education by simply subsidizing higher education might do more harm than good as it can lead to under-employment. Education, which is not properly linked to the productive functions in the society could boomerang in many ways. Some, who struggle to find jobs, would have actually got alienated from certain traditional sectors such as fishing, handicrafts and agriculture, in which their ancestors would have been gainfully employed. Although education can increase the supply of people with more skills suitable for business success, it can also decrease the supply of entrepreneurs by increasing occupational choices, unless education itself nurtures entrepreneurial values in the young minds.

There cannot be a single solution to the aforesaid challenge. What is required is a multi-pronged approach to promote `entrepreneurship’ through a planned action. Entrepreneurship needs to gain acceptance as a promising career option and not as a last resort for the unemployed.

Who are entrepreneurs? Are they born?

The definition of the word entrepreneur has evolved over time as the world’s economic structure has changed and become more complex. Since its beginnings in the Middle Ages the notion of the entrepreneur has been refined and broadened. In the middle of the 20th century, the notion of an entrepreneur as an innovator was established. This was followed by the introduction of the concept of ‘intrapreneur’, which meant an entrepreneur within an established organisation. Thus, going through a process of evolution, the term entrepreneur has acquired a broader meaning embracing concepts of creating a new business, risk taking, profit and growth orientation, urge to achieve, innovation and so on. Thus, entrepreneurship could be considered as the process of creating something new with value by devoting the necessary time and effort, assuming the accompanying financial, psychic, and social risks, and receiving the resulting rewards of monetary and personal satisfaction and independence[1]. It is a dynamic process of creating incremental wealth.

A consensus on the definition of entrepreneurship or entrepreneur may not be possible. However, what cannot be denied is the economic power of entrepreneurship, and its role in inspiring creative individuals to exploit opportunities and to take risks. The Green Paper “Entrepreneurship in Europe”[2] considers entrepreneurship not only as a driver for job creation, competitiveness and growth, but also as a vehicle for personal development, which can resolve many social issues. It qualifies entrepreneurship as a mindset, which can occur throughout the society at large. Entrepreneurship is as important a social need, as it is an economic one.

Considerable research has gone into what promoted entrepreneurship in different societies. McClelland (1953) in his article, ‘That Urge to Achieve’, underscored the `need for achievement’ and characterized people with high nACh[3] as preferring to be personally responsible for solving problems and for setting goals to be reached by their own efforts.[4] Through his experiments in 1964 and 1965 in India, it was concluded that entrepreneurs are not necessarily born in a society, but can be developed.

Such conclusions have been questioned in the background of the developing world where there are substantial limitations on the resource availability. In such an environment, high nAch, which is associated with competitive spirit, can be perceived as sin against one’s own fellows. Persons with high nAch may be frustrated and act counter-productively in societies that emphasise on a socialistic pattern. Scholars have subsequently argued that when resources are scarce, persons with high `need for cooperation’ will produce more than those with high n Ach[5].

However, largely based on the achievement motivation theory, Entrepreneurship Development Programmes (EDPs) were being conducted in different parts of the world. The concept of entrepreneurs as innovators may be difficult to be applied to less developed countries, where substantial `creative imitation’ takes place[6]. However, those engaged in such activities are entrepreneurs as well. Such early imitations, as in the case of Japan after the World Wars, or later in the case of China, have moved towards the frontiers of science and technology, and ultimately to indigenous innovation.

In reality, the skills associated with entrepreneurship are rare and limited in supply and the abilities of the entrepreneur are `so great and numerous that very few people can exhibit them all in very high degree‘ [7]. Entrepreneurs are also limited by the economic and socio-political environment, which surrounds them.

Entrepreneurial environment

Entrepreneurial culture begins with the person’s immediate family and society at large. The environmental forces ranging from purely cultural and social currents to inflexible government bureaucracy can restrain entrepreneurial driving forces. In a favourable entrepreneurial culture, an entrepreneur is seen as a `successful person’ and as a `wealth creator’ to the nation. Entrepreneurship will be seen as a means of achieving economic, social and political success not only for the entrepreneur, but also for the society at large. The younger generation growing up amidst such positive images and community value systems would prefer to be on their own feet. They will be enthused by the ample opportunities around.

The decision to leave a career and start a business is not an easy one. Individuals tend to start businesses in areas that are familiar to them. Research and development, and marketing are two work environments that have been particularly good in spawning new enterprises. Individuals who develop new product ideas or processes often leave to form their own companies. Such spins offs are possible from large organisations when some employees who gain expertise in certain areas leave to function as vendors to their former employer. Similarly, individuals in marketing, who become familiar with the market and customers’ unfilled wants and needs, start new enterprises to meet these needs. A significant number of companies are formed by people who have retired, or who have been fired. Being one’s own boss, being successful, and making money are all driving forces for entrepreneurship.

Risk-capital availability plays an essential role in the development and growth of entrepreneurial activity. More new companies form when seed capital is readily available. The role played by venture capital funds in IT start-ups worldwide needs no explanation. A literature survey of the current funding practices in some countries indicates two broad groups – (a) developed economies where the focus is on venture capital financing – mostly private and with very high levels of risk taking, and (b) the newly industrialized economies as well as the developing economies where the financial assistance largely comes through government supported schemes. The latter form of financial assistance by way of government soft loans and grants to support micro and small business ventures become futile exercises in the absence of a concerted effort to identify the right and potential entrepreneurs, and also assist them from concept to commissioning.

Stimulating entrepreneurial initiatives is a process that embodies multi-dimensional and calculated strategic choices. By encouraging entrepreneurial value systems in the society, governments can alter their country’s supply of domestic entrepreneurship. The various concepts and theories propounded by the researchers seem to indicate that the emergence of entrepreneurs in a society depends upon closely inter-linked economic, social, cultural and psychological variables. Improving the process of entrepreneurial development require enhancing the enterprise culture, eliminating entry and sustaining barriers and allowing innovative forms of entrepreneurship. Therefore, in a developing economy context, government intervention is significant, provided it can holistically address the stimulatory, support and sustaining elements of the development process (See Fig 1).

In short, the supply of entrepreneurship is determined by two broad factors – opportunity and willingness to become an entrepreneur. Opportunity is “the possibility to become self- employed if one wants to”. The primary factors affecting opportunity include business opportunity information, capital availability, ease of entry into the market, and the general macroeconomic environment. Willingness, on the other hand, is the relative valuation of work in self-employment compared to one’s other options for employment[8]. The supply of entrepreneurship is thus dependent on both individual level factors and general economic factors.

Entrepreneurship and economic development

The role of entrepreneurship in economic development involves more than just increasing per capita output and income; it involves initiating and constituting change in the structure of business and society. This change is accompanied by growth and increased output. One theory of economic growth depicts innovation as the key, not only in developing new products (or services) for the market but also in stimulating investment interests. The unique contribution of entrepreneurship is that it is a low cost and sustainable strategy of economic development, job creation and innovation. Entrepreneurship development is a highly leveraged strategy of development. Its multiplier effect is very large relative to each unit of governmental assistance. Tax holidays and subsidies to attract foreign investments are often more expensive than systematically nurturing local entrepreneurs[9]. Entrepreneurship is an effective method of bridging the gap between science and the marketplace, creating new enterprises, and bringing new products and services to the market.

Entrepreneurship development – some experiences

It has been generally accepted that the emergence of entrepreneurs in a society can be stimulated in very many ways, one of them being the Entrepreneurship Development Programmes (EDP). EDPs generally would include psychological exercises and games, presentation of business opportunities, guidance for market study, preparation of individual project schemes, input on functional areas of management, interaction with successful entrepreneurs, factory visits, etc. The effectiveness of these EDPs is better observed in the context of those places with relatively lesser entrepreneurial activities. The results of such a study conducted in one of the industrially backward southern states in India revealed the following.

An assessment of the success rate of 21 EDPs (with 482 participants) conducted over a period of two financial years revealed that, by the end of the third year of the conduct of the programmes, a maximum of about 33 per cent success rate was achieved[10]. Here, the word `success’ meant only the implementation of the project and not the health of the project. Typically, steep rise in the success rate was observed after the first year of training, which gradually increased by the end of the third year. Beyond this period, the success rate was found to stagnate. Even a 30 percent success rate is good enough from the point of view of its multiplier effect in ultimate employment generation.

One of the major findings of the survey conducted among the participants of the aforesaid EDPs was that, for all of them, `own industry’ or `own enterprise’ was practically an unheard concept while they were in the schools or even colleges. Majority of them considered this as a career option only after spending two to five years after their formal education. On an average, more than five years of an individual (in the sample studied) was found to have been wasted in job hunting before deciding to set up an industry. Even after having taken the decision to be entrepreneurs, 44.4 per cent considered salaried job as a better option, on account of social security and the innumerable procedural hurdles.

There is very little doubt that EDPs would play a significant role in creating first generation entrepreneurs. It will also equip these entrepreneurs to face the challenges of running businesses successfully. A successful entrepreneurship development is possible only if the development process is capable of addressing the issue as a multi-dimensional problem.

Government grants and soft loan schemes for small businesses and self-employment shall be linked to well-structured EDPs. The beneficiaries selected for such schemes of assistance shall undergo a mandatory EDP training before the funds are disbursed. Alternatively, the successful completion of an EDP in itself could be an essential prerequisite for selecting the beneficiary for financial assistance. Business promotional steps such as the incubators, mentoring and venture capital financing could also be linked to such EDPs. Over a period of time, EDP itself could be institutionalised as a perpetual mechanism under a designated agency.

EDP as a one-stop-shop support

During the training period itself, assistance could be provided to clear much of the governmental procedures for setting up a business. This could include anything from commercial or industrial licensing to submitting a loan application, depending on whether the candidates have finalized their project ideas or not. These services could be provided as on-the-spot clearances at the venue of the programme in a region, by inviting officers from the agencies involved, and is ideally done towards the end of the programme. The chances of project implementation and the successful operation of the enterprises created can be considerably enhanced if post-training support services are provided.

The success of the EDPs shall be judged in terms of parameters such as the number of entrepreneurs trained and assisted (financially), number of units implemented (within a time frame) and the number of units actually working (after a specified time period has elapsed).

Catching them young

The basic entrepreneurial qualities and value systems are better inculcated at a very young age, as part of the formal education system, preferably before the secondary school level. Entrepreneurship related topics shall be included at secondary school and college levels. EDPs should be seen only as a final round motivating or stimulating tool.

Primarily, school should not be seen as a place just for the three Rs [Reading, (W)riting and (A)rithmetic]. There are numerous other ways of touching the young minds, one of them being `crafts training’. Training related to crafts, arts, social service, and scouts & guides significantly contribute towards shaping the personality of the future generation. This has to be acknowledged as an inevitable component of formal education[11].

In many parts of the world, highly skilled crafts and art forms are at the verge of being extinct with the last generation of their proponents leading a hand-to-mouth existence. This has to be seen juxtaposed with the enormous amount of money spent by governments to preserve traditional crafts and skills within museums or through cultural festivals

The local craftsmen could be hired to impart regular skill training to schoolchildren as part of the co-curriculum activities. It may also be possible to start `Entrepreneurial Clubs’ in some schools wherein students are encouraged to practise these skills (such as note book making, painting, handicrafts, etc) to be commercially exploited through annual exhibitions or regular outlets within campuses. This would also go a long way in inculcating `business sense’ and `dignity of labour’ in the young minds; needless to say, the whole exercise would gradually revive a few dying traditional skills and crafts.

A university level entrepreneurial club could allow their students to continuously work on new product ideas for commercialization after graduation. Suitable faculty members could function as mentors, which, in turn, would enrich their expertise.

Adopting an Integrated Approach

It is almost certain that entrepreneurship development is not possible through a single means. What is necessary is to adopt a multi-pronged and integrated approach that would give substantial thrust towards creating an entrepreneurially active environment. Some such possibilities are indicated below.

Industrial Clusters

Creation of small and micro business clusters will go a long way in developing an entrepreneurially active environment in the neighbourhood. A few such clusters in different regions and with some sector focus could be created. Establishing common facility centers, common branding and common marketing are possibilities associated with such clusters. The common facilities could provide support for design, testing, quality control, marketing, preservation, skill training and so on.

In many countries, natural industrial clusters have formed in regions with concentration of skilled craftsmen. Rejuvenating these clusters employing new concepts as indicated above is a possible option. It should also be noted that, in the current context, an industrial cluster does not necessarily mean a sprawling campus. For instance, a cluster of micro-enterprises in the plastic sector or toy making is possible in a multi-storey building or even as a virtual cluster of household businesses.

New technically oriented companies often seem to start in clusters of related firms. By bringing some types of activities under a particular promotional scheme, even a virtual clustering is possible. The countrywide fruit processing and canning centre (as a common facility centre), coupled with the Agmark or FPO [12] have made many Indian women successful entrepreneurs. The `publicly certified innovative SMEs’ scheme of the Japanese government have revitalised the Japanese economy through the creation of many new businesses and jobs.[13]

Outworker production systems

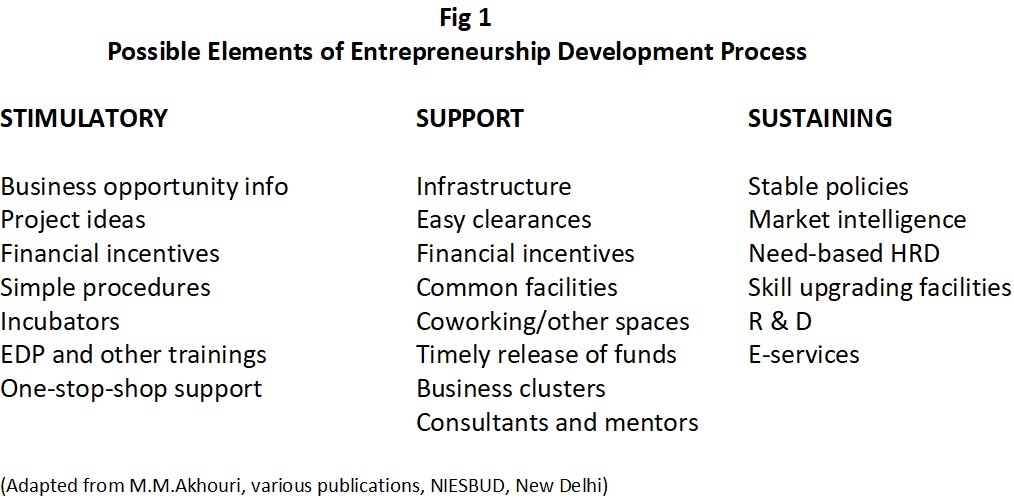

The concept of a mother unit’ and several satellite household units’ is an experiment, which has been successfully tried in some places[14] (See Fig. 2). Product innovation, design, tooling, assembly and marketing are the responsibilities of the mother unit. Members of the household unit would be trained to do a part of the processing using the machines provided by the mother unit under certain terms and conditions.

The mother unit is totally relieved of the mundane pressures of relatively trivial processes. Instead, it focuses on product innovation, quality enhancement and marketing. From a social point of view, this concept has facilitated a new means of developing micro-enterprises and entrepreneurship. The demerit, however, is the heavy dependency on the success of the mother unit, which is akin to the dependency associated with earlier experiments of developing ancillary units cluster to provide vendor support to large industries.

Encouraging household businesses

Living in the era of knowledge-based economy and virtual offices, it is not difficult to acknowledge the ability of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) to overcome temporal and spatial limits, thus setting up new modes of work and creating global workspace. But even without ICT, as explained earlier, there are innumerable ways in which businesses could function out of houses, thereby cutting down investments in fixed assets. In such situations the costs of failure are easily absorbable. Several brands of `pickles’ and `fruit preserves’ have grown big out of such household ventures.

The close-knit structure of the small-family enterprise is conducive for the incubation of ideas that are tested in the informal sector and later used to transform market products and processes. Women and young people are traditionally excluded from the formal sector and therefore their entrepreneurial ideas are locked out of the formal market. Since small-family enterprises in the informal sector typically involve women and youth participation, the informal sector can often serve as the outlet for their entrepreneurial ideas[15].

Government as a facilitator

Over the last two decades or so, the role of governments in the economy has considerably changed from regulation to facilitation. The wealth of data and information that flow into and that are generated in a governmental system often remain grossly under-utilized in the absence of adequate policies and systems for information management. Business organisations, on the other hand, may have to spend enormous amount of time and money to access this information for their decision-making. Governments, which reach out to the masses with information on investment opportunities and market intelligence reports would stimulate entrepreneurship.

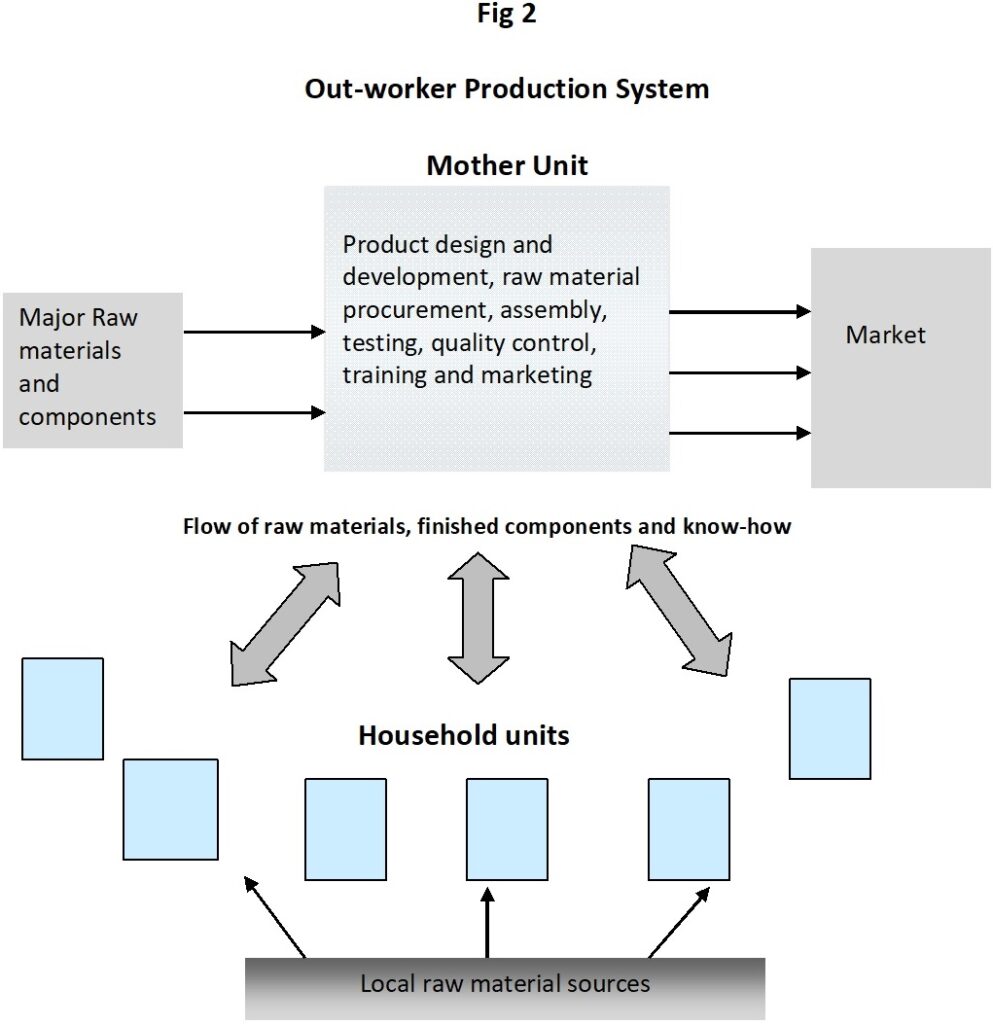

Business and technology incubators have become widely accepted means of nurturing first generation entrepreneurs, most often in partnership with the academia. This option needs to be employed with the best practices of providing not only the infrastructure but also ample techno-commercial linkages and handholding. An integrated model for entrepreneurship development in a highly simplified form is depicted in Fig 3.

Conclusions

Entrepreneurial resource is a vital component of economic development. Through the process of entrepreneurship, it is possible to augment capital formation, employment generation and ultimately economic development of a country. But entrepreneurship is not merely a driver for job creation and growth. It is a value system or mindset that a society develops, provided a multitude of inter-dependent factors are favourable. The emergence of entrepreneurs in a society, therefore, would depend on the socio-economic environment that is prevalent.

Sustainable development often demands indigenous entrepreneurship and innovation. The supply of entrepreneurship is determined by two broad factors – opportunity and willingness to become an entrepreneur. The former largely relates to the socio-economic environment, which provides the possibility to become self-employed if one wants to. Willingness is the relative valuation of work in self-employment compared to one’s other options for employment. Studies have shown that entrepreneurs are not necessarily born in a society but can be developed. Well-structured Entrepreneurship Development programmes (EDPs) can play significant role in achieving this. Many new development models comprising entrepreneurial clubs in schools and colleges, industrial clusters, outworker production systems, household industries, incubators, industry-academia linkages and common facility centers may have to be liberally employed.

However, entrepreneurial value systems need to be instilled in the young minds as part of the formal education. Entrepreneurship should become a preferred way of life in the young minds. Even in many developing countries, this mindset change has already happened. This is rather easy in the information era, because one can start really small and grow exponentially in no time. This potential to start with negligible investment and then to scale up fast once the opportunities are clear didn’t exist a decade ago. While entrepreneurship is apparently a people issue, only through a holistic and integrated approach capable of addressing a variety of aspects relating to the economic environment of the country, that a successful entrepreneurship development can be achieved.

References:

Cooper,A. and Folta, T. `Entrepreneurship and High-technology Clusters’, Handbook of Entrepreneurship, The Blackwell, Oxford, 2000

Drucker, P. Innovation and Entrepreneurship, W.Heinemann Ltd. , London, 1985

Eshima, Y. `Impact of Public Policy on Innovative SMEs in Japan’, Journal of Small Business Management, 2003, Vol.41, Iss.1, pp.85-93

Hisrich, R.D. and Peters, M. P. Entrepreneurship, McGraw Hill Irwin, New York, 2002. p.10 http://europa.eu.int/comm/enterprise/entrepreneurship/green_paper

Marshall, A. as cited by Burnett, D. (2000) in: http://www.technopreneurial.com

Mc Clelland, D.C. `That Urge to Achieve’, Think, Nov.-Dec., 1966, pp.19-23

Nafziger, E. W. `Society and Entrepreneur’, Modular Approach to Managerial and Entrepreneurial Skill Development, UNIDO, 1989

Ray, D. `The role of Entrepreneurship in Economic development”, Modular Approach to Managerial and Entrepreneurial Skill Development, UNIDO, 1989

Saeed, K. Towards Sustainable Development, Brookfield: Ashgate, 1998, pp. 235-259.

UNDP and Ministry of Labour & Social Affairs, Kingdom of Bahrain, Micro Start Project Evaluation Report, Nov. 2002

Van Praag, C. M. and Ophem , H. V. “Determinants of Willingness and Opportunity to Start as an Entrepreneur,” Kyklos, 1995, 48:4, pp.513-40. as cited by David Burnett (2000) in http://www.technopreneurial.com

Weber, M., The Protestant Ethic and Spirit of Capitalism, Allen and Unwin, London, 1956

[1] Robert D. Hisrich and Michael P. Peters, Entrepreneurship, McGraw Hill Irwin, New York, 2002. p.10

[2] http://europa.eu.int/comm/enterprise/entrepreneurship/green_paper

[3] Related to a score termed n Ach representing the `need for achievement’

[4] David C. Mc Clelland, `That Urge to Achieve’, Think, Nov.-Dec., 1966, pp.19-23

[5] E. Wayne Nafziger, `Society and Entrepreneur’, Modular Approach to Managerial and Entrepreneurial Skill Development, UNIDO, 1989

[6] Peter Drucker, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, W.Heinemann Ltd. , London, 1985

[7]Alfred Marshall as cited by David Burnett (2000) in: http://www.technopreneurial.com

[8] C. Mirijam Van Praag and Hans Van Ophem, “Determinants of Willingness and Opportunity to Start as an Entrepreneur,” Kyklos, 1995, 48:4, pp.513-40. as cited by David Burnett (2000) in http://www.technopreneurial.com

[9] Dennis Ray, `The role of Entrepreneurship in Economic development, Modular Approach to Managerial and Entrepreneurial Skill Development, UNIDO, 1989

[10] M.Sherif Aziz, ‘Approach to Industrialisation of Kerala: A Study with Special Reference to the Regional Characteristics of the State’, 1995

[11] We would put this activity and computer literacy more or less on an equal footing, as shaping up a citizen embodies building up `positive attitudes’. A `skill alone’ approach would be a mistake in the long run.

[12] Agmark and FPO are food products quality certifications

[13] Yoshihiro Eshima, `Impact of Public Policy on Innovative SMEs in Japan’, Journal of Small Business Management, 2003, Vol.41, Iss.1, pp.85-93

[14] M.Sherif Aziz, `Decentralised Planning for Industrial Development’, Dhanam, Kochi, Dec. 15, 1996

[15] Khalid Saeed, Towards Sustainable Development, Brookfield: Ashgate, 1998, pp. 235-259.