SATYAJIT RAY’S LITERARY WORLD

Vijayakrishnan is an award-winning film critic, writer and film maker.…

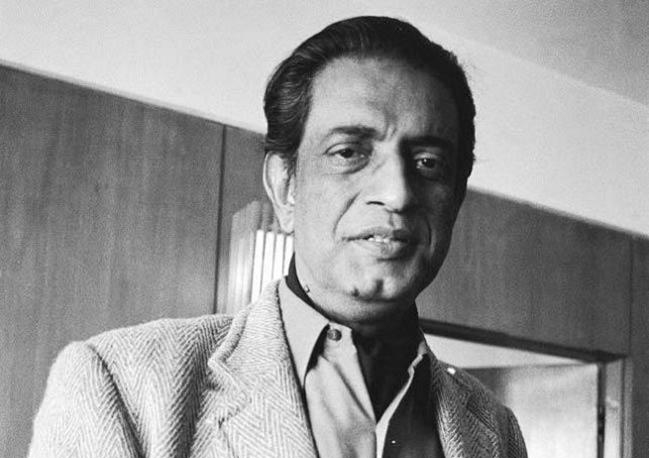

Along with Rabindranath Tagore, Satyajit Ray is revered not only as a genius but also for his unique prowess in different fields. Tagore was a poet, narrator, musician, illustrator, educator and many more, and so was Ray. Ray had similarly spread his creativity across a broad spectrum of activities. The world knows him as a legendary film maker, though he was first and foremost a writer and an artist at the same time.

Satayjit Ray was a doyen of Indian cinema. But he is also one of the finest film makers the world has ever produced. Besides being a film director, he was a scriptwriter, documentary filmmaker, author, essayist, lyricist, magazine editor, illustrator, calligrapher, and music composer – an all-in-one kind of personality.

Ray’s first film, Pather Panchali (1955), won eleven international awards. He had received thirty-six Indian National Film Awards, a Golden Lion (Venice), a Golden Bear (Berlin), two Silver Bears, and many other awards at international film festivals. India honoured him with its highest civilian award, Bharat Ratna, in 1992. In 2021, the country is celebrating this legendary film maker’s 100th birth anniversary. On this occasion, this article, written by Vijayakrishnan, tries to take us through the magnificent literary world of Ray. Vijayakrishnan is an award-winning film critic, writer and film maker.

He was a painter, who had his formal training at Santiniketan, He was a musician, a book designer, editor and publisher. In fact, Ray could have lived as a full-time writer, given the number of books he has written and widely sold too. Perhaps, cinema, a relatively new medium in those times, was so intriguing, overshadowing his reputation as a writer.

While being a short-story writer and a novelist, Ray had contributed regularly to various genre of literature. It looks as though he was keen on diversifying fictional writing. His literary world can be divided into three categories – stories, novels and film literature. These included experiences as well as reviews. His screenplays were indeed at par with original literary works. In fact, it is only when we read the screenplays of master filmmakers, we understand their grasp and skill in literature. Ray was no exception.

As for Ray, the screenplays were like an extension of his original literary work. He wrote the first story – Abstraction (English) – long before his first film was made, when he was in his twenties. As a matter of fact, Satyajit Ray couldn’t help writing in the kind of creative environment he had at home. In those times, a children’s magazine, pregnant with fascinating stories, was being created from this very house.

As a child, Ray grew up amidst the whole process of creating those stories and their illustrations. What a fertile ground for imbibing creative traits! It was only natural that this boy, full of stories in his mind, was allured by the literary world when he was quite young.

It was the children’s magazine Sandesh, and his grandfather Upendra Kishore Ray’s folktales that shaped Satyajit Ray’s literary skills. That influence is partly felt in his films too. A large part of Ray’s major films had the intense shades of neo-realism. A few others were direct reflections of contemporary realities expressed through new styles and techniques. The remaining had the tone of detective stories and fantasies from the folktales. If this has been the case with Ray’s films, his literary works have been predominantly folktales, fantasies, humour and detective stories.

Many of his fictional works were detective novels, short stories and science fiction. One gets the feeling that the character Sherlock Holmes had influenced Ray significantly. He also seemed to have followed the footsteps of Arthur Conan Doyle for some of his writings. Ray’s detective Feluda, resembles Sherlock Holmes, Pradosh Chandra Mittar being the real name of this character in the story.

Feluda also has a Watson – Tapesh Ranjan Mittar, also known as Topshe. But Ray had created a third character – a detective novelist by name Lal Mohan Ganguly. He also had a penname, Jatayu. These three formed the main characters in the fascinating Feluda stories.

Badshahi Angti, published in 1969, was the first Feluda novel. It is indeed interesting to note that Ray wrote one Feluda story every year, with the same commitment he had of making one film almost every year. Sonar Kella was the third novel in this series. It is through this work that the character Jatayu comes into picture. When Watson was replaced by a young Topshe, Ray had already deviated from Conan Doyle’s approach.

Somehow, Ray was also conveying the message that his detective novels are not only for adults but also for children. That’s what sets apart Satyajit Ray from Conan Doyle. He transformed detective stories into children’s stories, and most of the stories have the presence of child characters. In fact, in Sonar Kella, the central character itself is a child. In Joi Baba Felunath, it is a child who diverts the entire investigation.

Satyajit Ray’s complete collection of Feluda stories has been published in English and translated into various other languages. Through these stories, Ray is securing his place in children’s literature and detective fiction at the same time.

In fact, Ray wrote science fiction too, with the same ease and imagination embedded in his detective stories. Through his science fiction, he created a fascinating character named Professor Shonku, a character born long before Feluda. The first book in the Prof. Shonku series was published in 1965, and was titled Professor Shonku. Though Ray authored six books with Shonku as the central character, he never made a film out of any of these stories. Sandip Ray, his son, later retold some of these stories as cinema and telefilms.

Before the birth of the character Prof. Shonku, Ray had written a science fiction titled Bankubabur Bandhu. This is the story of an alien that loves others and gets loved too. In the late 1960s, Ray was set to make a film titled The Alien, perhaps, based on this character. It was to be co-produced by Columbia Pictures, but did not materialise. It may not be out of place to consider that this initiative would have influenced the making of ET and Alien, much later, by Steven Spielberg.

In addition to Feluda and Prof. Shonku, Ray had created another protagonist in many stories – Tarini Khuro, the story teller. Khuro was engaged in fifty-six types of work in thirty-three cities. The children called him Tarini uncle. Children often swarmed around him when he returns after his nomadic pursuits. He would then tell stories of ghosts, valour and humour, in the guise of own experiences.

In the midst of all these multifarious activities, Ray even found time to translate his favorite writers’ works into Bengali. This included the works by Conan Doyle, Ray Bradbury and Lewis Carroll. He saw children who read Sandesh as the main readers for his stories and therefore, he did not venture into novels in the same style of his important films.

Ray’s first contribution to film literature was through the book, Our Films Their Films. He had a habit of writing notes about cinema long before the book was published. He was a regular contributor to major newspapers, sometimes to the letters-to-editor columns, writing about the latest trends in cinema and about contemporary filmmakers. At times, these letters were the subject of heated debate. In this way, he was able to approach films with the perspective of a critic. He sharply criticised the shortcomings of the Indian New Wave, as it emerged.

Later, he developed these arguments into essays. Similar critiques can be found in his Bengali book Bijoy Chalachithra, which he wrote almost at the same time as Our Films Their Films. Ray, being one of the best children’s writers in Bengali, couldn’t help but write a book on cinema for children too. Eki Bole Shooting is his book on filmmaking for children.

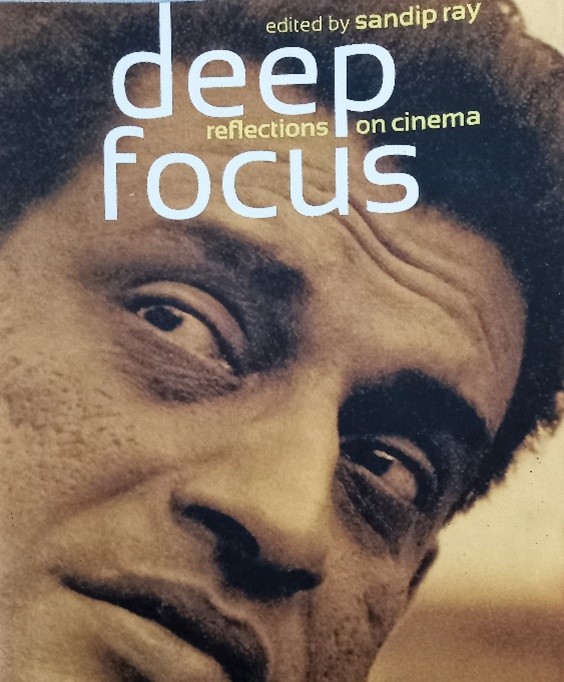

After his death, led by Sandip Ray, attempts were made to publish Ray’s unpublished essays in a book form. The result was the book, Deep Focus: Reflections on Cinema. The first article in this collection is National Styles in Cinema, an article Ray wrote in The Statesman in 1949, even before he became a filmmaker. Another article titled Our Festivals Their Festivals, again published in 1982 in the same newspaper, is the 22nd and the last article in this collection. This collection also included articles such as The New Cinema and I, and Under Western Eyes, that had some controversial statements.

Some of the experiences narrated in Deep Focus are interesting to read, leaving us a bit disappointed that we didn’t get an autobiography from this master craftsman. That said, Ray had indeed shared his childhood experiences with utmost simplicity and humour demanded by a children’s book, in Childhood Days.

If screenplay writing can be considered as part of literature, then, Satyajit Ray is a unique writer in that genre. Only a director with ample literary skills can be a scriptwriter himself. Others can collaborate with a scriptwriter to develop and document his ideas. If even that isn’t possible, one can fully entrust the script writing to another person. Ingmar Bergman was a filmmaker who believed that cinema has nothing to do with literature. Therefore, he did not believe in adapting literary works into films. Instead, he always used original screenplays. Yet, while reading his scripts, the reader is often led to a magical literary experience. It will convince readers that Bergman has a place on the league of writers, though Bergman himself wouldn’t make that claim.

A large part of Satyajit Ray’s screenplays were conceptual adaptations of works by eminent writers. Excluding these screenplays and those based on his own literary works, there are many of his works that are originally film scripts. Kanchenjunga was the first among these, and was different from his scripts until then. It was predominantly conversational. Although prepared for a film, it was written with literary principles in mind.

The short-films Two and Pikoo were also original stories written for film making. However, his film Nayak can be described as a literary work that became a movie. It is a brilliant portrayal of the protagonist’s identity through dialogues, with emphasis only on two characters. Shakha Proshakha, on the other hand, was a Tagore-style family narrative.

Manomohan Mitra in Agantuk is, in fact, a reflection of the character of Tarini Khuro he created in literature. It is said to be based on Ray’s short story Atithi, which is a literary work full of autobiographies and childhood memories

Thus, Satyajit Ray was an unusual master craftsman who demonstrated unparalleled confluence of creative abilities. While he lived more as a renowned film maker, after his death, the stories that he left behind were more than enough material for producing many fascinating films and telefilms.

(Note: Translated by: Sherif Aziz. Unless mentioned, images and figures are as provided by the author)

What's Your Reaction?

Vijayakrishnan is an award-winning film critic, writer and film maker. He is a walking encyclopedia on world cinema. In 1981, his book on films titled Chalachitra Sameeksha won the Indian National Film Award under the category - The Best Book on Cinema. Thereafter, he has won several national and regional awards for books on films. Securing a place in Malayalam cinema, Vijayakrishnan made his debut film Nidhiyude Kadha in 1986. After a gap, he made the film Mayoora Nritam in 1995, and subsequently entered the mini-screen Industry. He made fifteen TV serials, nineteen tele films and 9 documentaries. In 2009, he directed the film Dalamarmarangal , followed by Umma in 2011. His latest film Ilakal Pacha Pookkal Manja, made in 2017, is a children’s film. All the while, his literary pursuits continued unabated producing fourteen fictional works, twenty-three books on films, two children’s books and one literary criticism. Vijayakrishnan has been a member of the Indian Central Board for Film Certification, Director Board Member of Kerala State Film Development Corporation and Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. He has been a member of the Board of Studies in Thunchath Ezhuthachan Malayalam University and a governing council member of Kerala State Chalachitra Academy. He was a member of the Kerala State Film Award Committee and the Indian Panorama Selection Committee for Filmotsav 1986. He was a jury member of Indian National Film Awards 2015 and 2019, and the Chairman of the Kerala State Award Committee for books on Cinema.